A significant dose of reality for me, and I bet for several radarmen, came on 2 July when we saw our first MiGs . . . on radar. MiGs were the then-Soviet jet aircraft flown by the North Vietnamese. The variant flown at that time was, I believe, the MiG-17. “[Seeing MiGs on radar] was actually fairly exciting,” I noted, with perhaps a bit more nonchalance than was real, in my journal. “They came down from Hanoi (Bullseye), then turned back.” They reappeared in the same fashion on 4 July, maybe to note the holiday.

I was especially busy, getting the Intel shop going. I was staying up until 0230 or 0300 most nights, preparing information for the day ahead. Occasionally, I also had to brief the Commodore (Commander Destroyer Squadron Seven) onboard and his staff at 0600.

Crossing the Pacific, we had replenished supplies in Panama, Hawaii, Guam, and Subic Bay, with supplies being loaded on board while in port. On line, we conducted “underway replenishment” (UNREP) and “vertical replenishment” (VERTREP) for the first time. Indeed, on 5 July, we did both UNREP and VERTREP in the morning, as well as conducted an “ASCM” exercise (I’m guessing that stands for “anti-submarine countermeasures,” but I hope someone can help me out with that acronym).

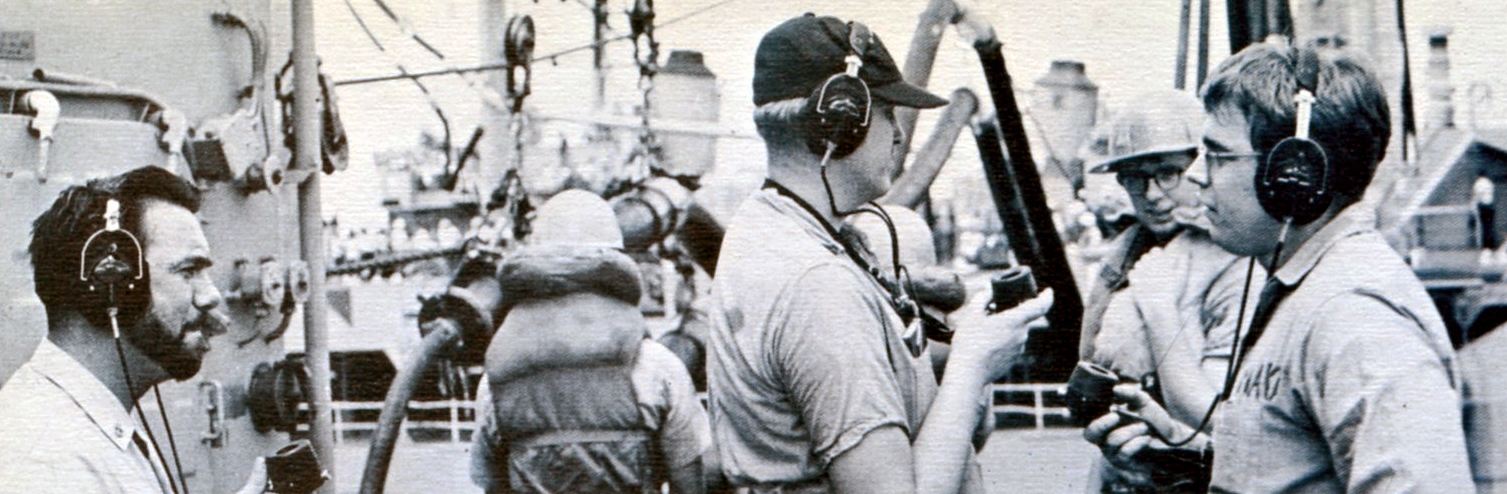

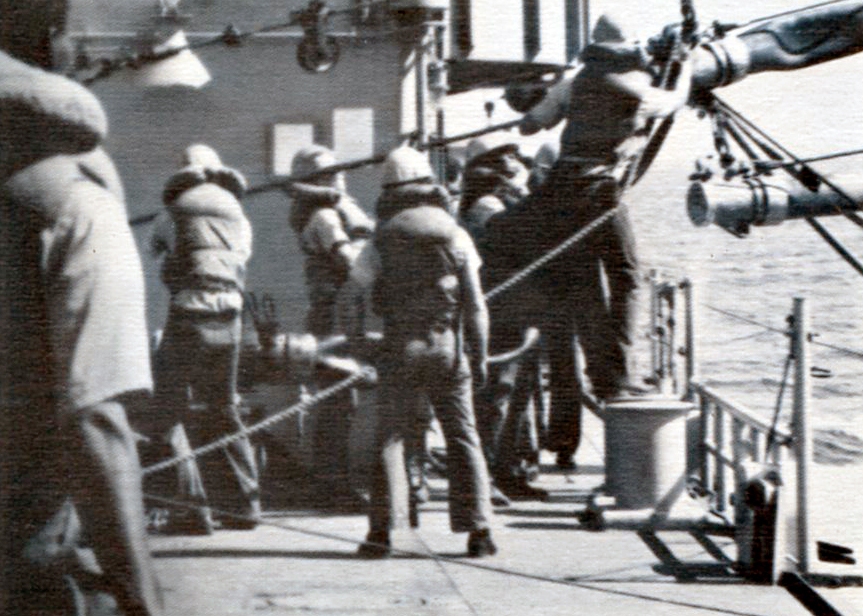

UNREP particularly was a complicated series of operations. The supply ship would be on a particular course and speed. Biddle would have to approach from the stern of the supply ship, coming up alongside at the proper distance and maintaining the same speed. (That evolution was one reason I was happy to stick to occasional man overboard drills to drive the ship.) I would have expected the supply ship to fire one or more “shot lines” across to Biddle, which would allow a messenger line and then transfer rig lines to attach file hoses, etc. Our cruise book, however, shows one of Biddle‘s crew firing a shot line. (Again, assistance from someone more involved in the evolution is most welcome.)

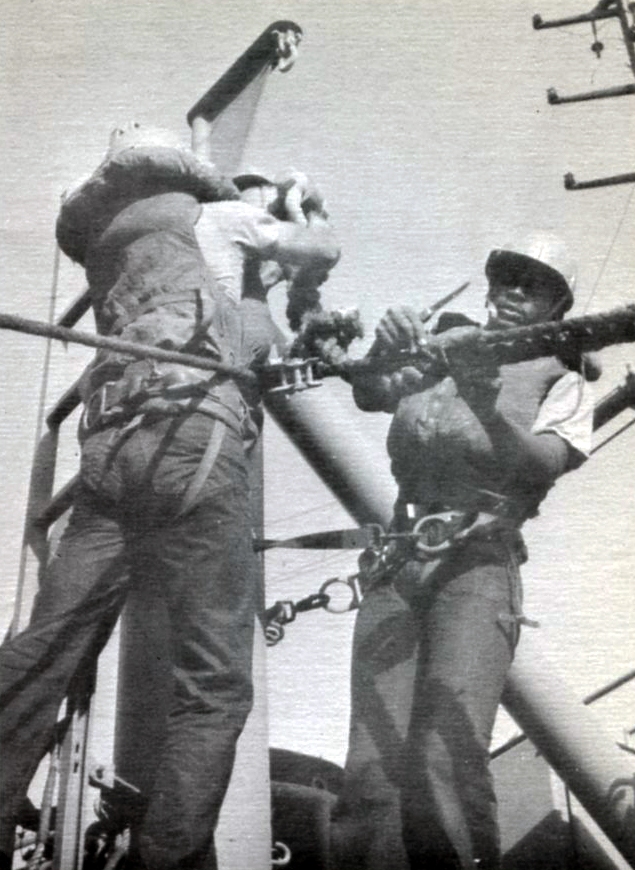

Sometimes UNREP was how we would receive mail, movies, etc. VERTREP, which involved helicopters approaching Biddle‘s stern, hovering over the helo deck, and then lowering supply containers was another efficient way to deliver some cargo. Sometimes both operations took place simultaneously. The danger of two ships operating so closely and the complexity of the operation overall made for an “exciting” morning. Connecting had its own level of excitement and complexity, but disconnecting was “extra special.” All in all, I think UNREP was most appreciated after it had concluded without incident.

Here is a gallery of Biddle cruise book photos showing UNREP and VERTREP.