On this date in 1969 (a Monday then), at about 1000 (10 am to you civilians), USS Biddle eased away from Pier 23, Naval Station, Norfolk, Va., to begin a seven-month deployment to the Western Pacific (WESTPAC).

For those of us undertaking our first deployment, this was a big deal. Looking back, I consider the cruise the greatest single adventure of my life. (I think being a father has been my greatest adventure overall.) Based on part of my journal entry that day, however, my focus seems to have been on my stomach.

“Hadn’t thrown up as of 1830. (Didn’t eat much supper.) 1900 — hit the sack. Beginning to round [Cape] Hatteras. Oh God!”

I had never before been to sea. I had rarely been on a boat and certainly not out of sight of land. My ignorance about what going to sea entailed and my inexperience fueled my concern about becoming seasick and embarrassing myself. One of the most significant differences between being at sea and on land is that, at sea, the deck (floor) is never stable. Below is a short video taken from a wonderful collection of scenes shot on the deployment by GMG2 George Boyles and GMG2 Jerome Kuczmarski, and edited by Boyles. (These were taken on 8mm film, then transferred to video, then digitized, so technical quality has been diminished.) The beginning shows the wake behind the ship and the second shows the ship rolling, i.e., moving side-to-side along its longitudinal axis.

My shipmates and I were now embarking on a voyage of thousands of miles through the Caribbean Sea, into the Pacific Ocean, and on to Hawaii before setting foot on land again. (We had expected to have liberty in Panama City, but, as you’ll learn, that was not to be.)

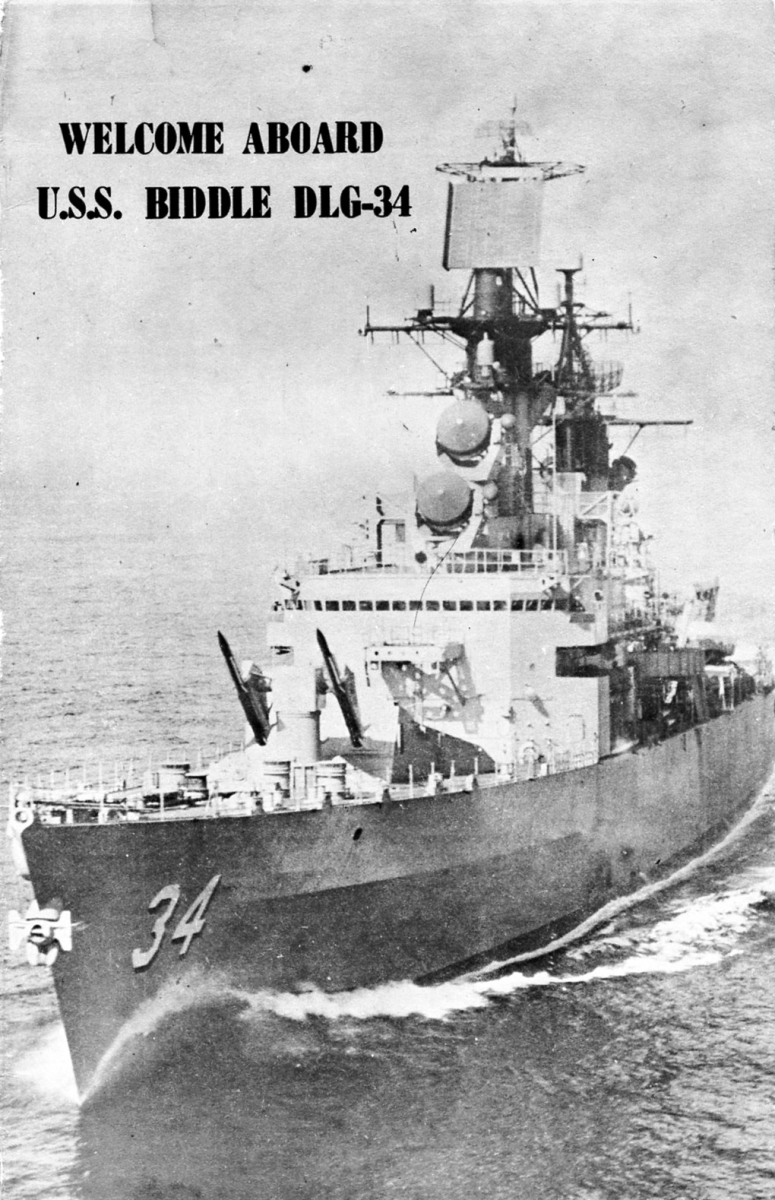

Looking again at the picture at the top of this post, it’s interesting to note two of the ships also on that pier. The ship inbound of where Biddle had been was the German destroyer Lütjens (D-185). Across the pier was USS Norfolk (DL-1), the Navy’s first Destroyer Leader. The Norfolk had been launched in 1951 and was decommissioned in January 1970.

As one of the many unmarried sailors on board, I had no one on the pier saying goodbye. Many others did, however, and I only later came to appreciate the sacrifices they and their family members made during such deployments. While the ship was in radio communication with “the Navy,” individuals then had no personal means of electronic communication. Twelve babies were born while their dads were away at sea during this deployment. One father missed by only about a week, as his child was born on 2 June. The captain authorized him to use the ship’s communications system to connect with his wife in the hospital.

I stood my first watch in CIC that day as well. I’m sure it was in a very secondary role, observing the experienced watchstanders.

Day 1 — 204 to go!